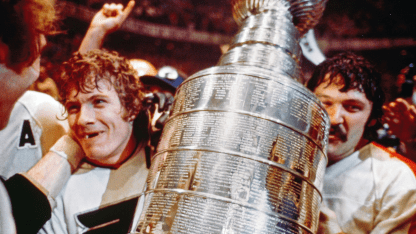

The afternoon of May 19, 1974, is one that will live forever in the annals of NHL history and the history of the Philadelphia Flyers franchise. On that day, the Flyers became the first expansion to win the Stanley Cup. The Flyers, of course, went on to win back-to-back Stanley Cup championships amid three straight trips to the Cup Final and six consecutive playoff runs to at least the semifinals.

Entering the 1974 Final against the Boston Bruins, the Flyers were the underdogs. The “Big, Bad Bruins” had won the Cup in 1969-70 and 1971-72, and remained a powerhouse team led by the likes of the legendary Bobby Orr and Phil Esposito. Boston was the heavy favorite to beat the Flyers.

For the Flyers to defeat Boston and win the Cup, winning at least one game in the Boston Garden — and being perfect on home ice at the Spectrum — was a must. The Bruins held the home-ice advantage heading into the series. The Flyers won their first-ever game in Boston, way back on Nov. 12, 1967, but had not since won another road game against the Bruins.

In order to reach the Final, the Flyers (112 regular season points, first place in the Western Division) swept the Atlanta Flames in four games, and then survived a seven-game war of attrition with the New York Rangers in which the home team won each game of the series. The win was costly for the Flyers, however. All-Star defenseman Barry Ashbee suffered a career-ending eye injury in Game 4. Hard-checking energy-line winger Bob Kelly sustained a season-ending knee injury.

Prior to the start of the Cup Final, Hockey Hall of Fame coach Fred Shero had two surprises in store: one for the public, and one for his Flyers players.

“When we got to Boston, I looked in the newspaper,” Flyers Hall of Fame defenseman Joe Watson recalls. “There’s a quote in there from Freddy. It said something like, ‘We’ve already beaten a tougher team than Boston. The Rangers were a more dangerous opponent. We’ll be fine.’ I went to Freddy and said, ‘Why would you say that?’ He said it was to get under the Bruins’ skin and to make our guys confident we could do it.”

The other surprise came in a pre-series team meeting. Shero advised his players to repeatedly dump the puck into Orr’s corner throughout the series.

“Freddie said, ‘Just make sure you get a piece of him. It might not work at first, but keep doing it, anyway.’ I thought that was the opposite of the way we should play against Orr. Everyone else tried to keep the puck away from him as much as possible,” recalled Joe Watson, who was Orr’s defense partner and housemate in Boston during the 1966-67 season.

The purpose of the strategy was to try to wear Orr down over the course of the series. It was a risky approach to let Orr — a magician with the puck and a very strong player from a physical standpoint — be the first Bruin to gain possession. However, nothing else had seemed to slow him down effectively, and Orr was already dealing with well-known knee problems. Thus, Shero’s hope was to tire Orr out over the course of a six-game or seven-game series.

Game 1 at the Boston Garden was on May 7, 1974. It was a heartbreaker for the Flyers. Goals by Orest Kindrachuk and Bobby Clarke erased a 2-0 deficit. The game seemed to be headed for overtime when Orr scored with 22 seconds left in the third period to lift the Bruins to a 3-2 victory.

Game 2, on May 9, was a landmark in Flyers history. The Flyers once again fell into a 2-0 deficit. Clarke narrowed the gap to one goal early in the second period, but the Flyers still trailed entering the final minute of regulation. Just in the nick of time, Andre “Moose” Dupont scored at 19:08 — assisted by Clarke and Rick MacLeish — to force overtime. Finally, at 12:01 of sudden death, Clarke took a pass from Dave “The Hammer” Schultz and scored off his own rebound after being initially stopped by Boston goalie Gilles Gilbert. Clarke’s jump for joy in celebration of his game-winning goal is perhaps the most famous freeze-frame moment in Flyers history.

The Flyers had their indispensible win in Boston. But they knew there was no margin for error when the venue shifted to the Spectrum. They were confident, however, having gone 28-6-5 at home during the regular season and 6-0 up to that point of the playoffs.

Game 3 was played on May 12. The Bruins struck first on a John Bucyk goal but Philly scored twice on tallies by Tom Bladon (power play) and Terry Crisp to take a lead to the first intermission. The second period was scoreless. In the third period, goals by Kindrachuk and Ross Lonsberry gave the Flyers some breathing room.

Hall of Fame goaltender Bernie Parent (24 saves on 25 shots) took care for the rest. The Flyers now had a two games to one lead in the series.

Game 4 was a rough-and-tumble affair with several fights and a parade of Flyers and Bruins skating to the penalty box in the first period. The teams traded off two goals apiece, with MacLeish (power play) and Schultz staking Philly to a 2-0 lead only for Esposito (power play) and Andre Savard to answer back for Boston.

The second period was a little calmer. Parent helped the Flyers get through an important penalty kill, and there were a couple of coincidental minors from after-the-whistle scrums but no fisticuffs.

The third period was scoreless for 14-plus minutes. Finally, future Hockey Hall of Famer Bill Barber restored a 3-2 lead for Philadelphia. Dupont added some insurance, and Parent finished with 28 saves on 30 shots. The Flyers were now in the driver’s seat, with a 4-2 win in the game and a three games to one lead in the series.

The series moved back to Boston for Game 5 on March 16. The Flyers did not want to give the Bruins renewed life in the series, but it wasn’t to be. The game was tied at 1-1 in the second before Orr took over on the way to a three-point game (two goals, one shorthanded assist). The Bruins prevailed, 5-1, to send the series back to Philadelphia.

Over the course of Shero’s coaching career in Philadelphia, his Flyers players had grown used to him writing pregame messages on the blackboard in the dressing room. On this Saturbday morning prior to the start of Game 6, the message read, “Win today, and we walk together forever.”

“I don’t think any of us really thought about it too much at the time,” Barber recalled in 2019. “But Freddy knew what he was talking about.”

An overzealous Dupont took an interference penalty in the opening minute of the game. Parent and the penalty killers stepped up to keep the game scoreless early. Philly got through a second kill midway through the opening stanza.

At 13:58 of the first period, the Flyers went on their first power play. Terry O’Reilly went off for hooking. On the ensuing 5-on-4, the Flyers’ MacLeish won a faceoff, and the puck went back to Dupont at the left point. MacLeish moved toward the slot.

“The puck was a little bit on its edge,not sliding flat,” Joe Watson recalled. “Freddy always preached, ‘Don’t shoot a rolling or bouncing puck.’ Thank goodness, Moose shot this one.”

From the slot, MacLeish deflected the puck and it went past Gilbert at 14:48 for his 13th goal and 22nd point of the 1974 playoffs. The Flyers had a 1-0 lead but precious little margin for error as no further scoring ensued over the remainder of the first period.

The second period was scoreless. The Flyers once again killed an early-period Dupont penalty but were unable to add to their lead on a couple of power plays and several scoring opportunities. Through two periods, Parent had turned back all 25 shots he’d faced. Gilbert had allowed only the unstoppable MacLeish tip-in among the 22 Philadelphia shots.

In the third period, the checking was very tight on both sides. The Flyers took no chances and the Bruins grew frustrated as they were unable to find room to operate. The teams combined for nine shots on goal: five by Boston and four by Philly.

At 17:38, Clarke broke loose. In desperation, a pursuing Orr grabbed and spun around the Flyers’ captain. Referee Art Skov’s arm went up, and Orr was penalized for holding. It was an obvious penalty, but a frustrated Orr argued the call to no avail.

The Flyers approached the power play very cautiously. The most important aspect was that two precious minutes ticked off the clock. Orr exited the box with 22 seconds left in the game.

In perhaps the most famous broadcasting sequence of his legendary career, Gene Hart called down the remaining time this way: “Thirteen seconds left in the game, 10 seconds… Orr shoot it down the ice, Parent makes the save!” Note: In reality, the puck went wide of the net for a potential icing, but Hart was caught up in the drama of the moment.

With his inflection rising to a crescendo, Hart proclaimed, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Flyers are going to win the Stanley Cup! The Flyers win the Stanley Cup! The Flyers win the Stanley Cup! The Flyers have won the Stanley Cup!”

Behind the net as the celebration commendenced, Flyers checking center Crisp convinced linesman Neil Armstrong to hand him the puck.

“It means more to me than it means to you,” Crisp explained. The linesman complied. Fifty years later, Crisp still has the puck. It’s one of his most prized possessions.

Bedlam ensured. Hundreds of Flyers fans — many of whom didn’t even have tickets to the game but had been listening to the game on the radio and entered the Spectrum through unlocked doors — rushed out onto the worn-out ice surface. One young fan, clutching a champagne bottle, even got himself into the handshake line on the Flyers’ side.

The mob of fans on the ice hampered the Cup presentation ceremony, and prevented a proper victory lap by the entire Flyers team after Clarke and Parent lifted the Cup. Flyers players, including Schutz and Bill Clement, had to clear a path before the celebration continued in the locker room.

After celebrating with his teammates and his father in the locker room, Joe Watson met up with Orr in a room adjacent to the locker room. Orr, who served as the best man at Watson’s wedding several years earlier, graciously congratulated his old friend.

“You guys wore me out,” Orr confessed. “I’m exhausted.”

Shero’s pre-season strategy had paid off. With the Cup on the line for the Flyers, the other team’s Hall of Fame defenseman had finally run out of gas.

The next day, the entire city of Philadelphia celebrated the Flyers with a massive parade down Broad Street. An estimated two million people attended. Just seven years earlier, less than 100 people attended a “Welcome the Flyers” parade held before the first home game in club history.

The contrast couldn’t have been starker. It wasn’t lost on the holdover players from the inaugural season: Gary Dornhoefer, Joe Watson, Parent (in his second stint with the Flyers), and Ed Van Impe.

“Back in that first year, we didn’t know if there’d even be a second year,” Watson recalled. “We had maybe a dozen people who stood to watch that parade. The major didn’t show up for the reception at City Hall. Later that season, part of the roof blew off at the Spectrum. We were like a bunch of vagabonds the rest of the season. So when we won the Stanley Cup seven years later, and there’s two million people on Broad Street, it was like there had been a miracle in seven years.”